One common use for bioassays is to test manufactured biologic products before they are released to the wider consumer market. While all bioassays used for this purpose will have undergone stringent testing and validation, it is vital that their ongoing performance is closely monitored to ensure that any changes in the assay system do not lead to incorrect decisions about the quality of the manufactured product. An important tool to implement this monitoring is Statistical Process Control (SPC), which uses control charts to track assay performance against a set of pre-defined rules.

SPC is a well-established technique which is used across a wide range of manufacturing processes. Monitoring bioassays, however, introduces challenges which can come into conflict with the underlying statistical basis of SPC. For example, replication within bioassay runs can introduce correlations which violate key assumptions when setting up control charts. Here, we’re going to investigate the origin of these correlations, discuss how they can lead to problems when monitoring assays using SPC, and examine how these problems can be countered.

Key Takeaways

-

Replication across plates within an assay run can introduce strong correlations that violate the independence assumption underlying standard SPC control charts, leading to underestimated variability and inflated false alarms.

-

When correlated plate-level data are treated as independent observations, moving range estimates of variability become artificially small, resulting in overly narrow control limits and excessive Type I errors.

-

By averaging correlated plate-level parameters into a single assay-level observation, independence is re-established, control limits become meaningful, and SPC once again reflects true assay performance.

Assay Monitoring and SPC

While the testing required for an assay to form part of a manufacturing workflow is extensive, it provides only a time-limited guarantee of the performance of the assay. We can verify that the assay performs within defined limits when validation takes place, but can this be taken as read for the lifetime of the assay? Unfortunately, change is inevitable in even the most stable of assay systems – reference drift, for example – meaning routine checks are required to ensure that the assay continues to provide high quality results.

USP <1220> defines Ongoing Procedure Performance Verification (OPPV) as stage 3 of the analytical procedure lifecycle, while USP <1221> provides guidance for its implementation. The goals of OPPV are to provide a proactive approach to detect and correct drifts, shifts, and/or unusual variability in the assay system to prevent them from escalating to significant deviations. This allows confirmation that the procedure continues to meet the performance requirements necessary to maintain a high-quality product.

Statistical Process Control (SPC) is a commonly used tool for implementing OPPV. SPC involves plotting key performance metrics on control charts and comparing them against control limits. Along with a set of rules defining the expected behaviour of the assay, this allows for changes to the assay system to be easily identified. SPC should only be implemented when the assay method is stable and not expected to undergo any further planned changes. The control limits and rules can and should, however, be informed by historical data from, for example, the validation of the assay.

SPC is an example of a quantitative approach to OPPV. These use numerical metrics to monitor an assay process. Metrics might include one or both of

Measures of variability: e.g. variability of replicates, Geometric Coefficient of Variation (GCV) of control sample measurements, the precision of the final reportable value.

Measures of System and Sample Suitability: e.g. reference model parameters, control sample potency, or parallelism metrics.

These are all approaches to measuring the performance of the assay system. If they continue to fall within the expected behaviour of the assay, then it is reasonable to conclude that the assay remains capable of providing results with acceptable accuracy and precision.

Note that the final reportable value of the assay, such as test sample relative potency, would not be an appropriate metric for use in SPC. OPPV asks whether the assay system continues to provide high-quality results for the final reportable value, not whether the final result falls within the bounds we expect. An assay which is performing entirely as expected might return an unusual reportable value. Indeed, this likely indicates a quality issue with the test sample, which is what we’re trying to detect! If we were to use the reportable value as an SPC metric, we might throw out this result citing a problem with the assay system, which would be entirely counterproductive.

SPC is not the only recognised approach to OPPV. Semi-quantitative methods are processes which do not require acceptance criteria or control charts but, nevertheless, provide a method for early identification of increases in assay failure rates. Examples include conformity indicators, which evaluate the frequency of Out-of-Spec (OOS) results for signs of performance problems, and validity indicators, which track the number of system and sample test failures over time to check for changes in the frequency of assay failures.

Control Charts and Limits

Here, we’re going to focus on quantitative methods, specifically those which use SPC. As mentioned, SPC employs control charts to track the performance of an assay through one or more parameters. For our purposes, we’ll use the slope parameter, ![]() , of the reference model. There are several ways we can use this parameter in a control chart. The simplest is to plot the raw parameter value, but an alternative might be to use a moving range. This is calculated by finding the difference between consecutive values.

, of the reference model. There are several ways we can use this parameter in a control chart. The simplest is to plot the raw parameter value, but an alternative might be to use a moving range. This is calculated by finding the difference between consecutive values.

Once the parameter and charting method have been chosen, the next step is to calculate control limits. Control limits are used to assess whether a process is in control, and are plotted as horizontal lines on a control chart. We define control limits based on the risk of making an incorrect decision, or error. There are two possible types of errors:

- Type I error: a false positive. When an investigation is triggered when the process is not out of control

- Type II error: a false negative. When a true change to the behaviour is missed.

To avoid Type I errors, we could set our control limits to be far apart. This means that only the largest changes in the behaviour of the assay would trigger an investigation, minimising the false positive rate. However, this would increase the rate of false negatives, as some true changes to the assay system may not be large enough to trigger an investigation. Indeed, to minimise the Type II error rate, we would want to move the control limits close together so no change was missed. But, of course, this would lead to an increase in the false positive rate!

Setting control limits, therefore, will always involve a balance between the Type I and Type II error rate. For individual parameter values which are assumed to follow a normal distribution (more on this later), the control limits will be set based on the mean (![]() ) and the standard deviation (

) and the standard deviation (![]() ) estimated from collected historical data. Generally, two sets of limits are set: alarm limits and alert limits. A value outside the alarm limits indicates the need for an immediate investigation, while a value outside the alert limits is a sign of a potential change in the assay system which may warrant an investigation depending on the rules chosen for the SPC. The limits are defined as follows:

) estimated from collected historical data. Generally, two sets of limits are set: alarm limits and alert limits. A value outside the alarm limits indicates the need for an immediate investigation, while a value outside the alert limits is a sign of a potential change in the assay system which may warrant an investigation depending on the rules chosen for the SPC. The limits are defined as follows:

![]()

![]()

For SPC, the standard deviation of the observations is often calculated using the moving range. The moving range is defined as the absolute difference between two consecutive observations. If the average moving range (often represented as ![]() ) is large, then the data is highly variable: there is typically a large difference between consecutive observations. If the average moving range is small, then the data is less variable, as there is typically only a small difference between consecutive observations. Using this approach, the control limits can be calculated as

) is large, then the data is highly variable: there is typically a large difference between consecutive observations. If the average moving range is small, then the data is less variable, as there is typically only a small difference between consecutive observations. Using this approach, the control limits can be calculated as

![]()

![]()

![]() is a control chart constant which defines the proportionality between the average moving range and the standard deviation of the data. The exact value of will depend on the number of observations used in finding the moving range.

is a control chart constant which defines the proportionality between the average moving range and the standard deviation of the data. The exact value of will depend on the number of observations used in finding the moving range.

From the properties of a normal distribution, we know that 95% of independent observations of a normally distributed parameter will fall within two standard deviations of the mean, while 99.7% will fall within three standard deviations. This means that, for an unchanged assay system, approximately 99.7% of parameter values will fall inside the SPC alarm limits. We also gain a good understanding of the likelihood of a Type I error – an observation falling outside the alarm limits by chance – which will be approximately 0.3%. From this, we can estimate that one out of every 370 observations of our parameter in an unchanged assay system is expected to fall outside the alarm limits.

Flawed Assumptions

One key assumption which underlies the properties of control charts is independence. For data to be independent, we require that no observation of the control parameter should give us any information about future observations of that parameter. Observations which violate this assumption are said to be correlated. Variability between correlated observations is usually lower than that between non-correlated observations.

In many manufacturing scenarios, this assumption is very robust – there’s no reason to expect the diameters of screws coming off an assembly line to be correlated, for example. The situation for biologics manufacturing, however, is more complicated. Compared to many other measurement techniques, bioassays are highly variable instruments. That means that replication of samples – whether within a single plate or across several – is an essential tool for increasing the precision of bioassay measurements.

This replication can challenge the independence assumption underlying the statistical basis of SPC. A commonly used assay format is to combine the results from three plates into a single reportable result. These plates will usually be run on the same day and by the same operator. For the sake of clarity, we will consider an “assay” or “run” to be this combination of three plates.

Often, the control parameter – e.g. the reference ![]() parameter – for each of the three plates is included as an independent observation on a control chart. On the face of it, this may not seem like a problem – they are from different plates after all. But all is not as it seems. There are likely to be correlations between plates combined to produce a reportable result due to being run on the same day and by the same operator. That means the observations of the control parameter from these plates are more likely to be similar to each other than those from other randomly selected observations.

parameter – for each of the three plates is included as an independent observation on a control chart. On the face of it, this may not seem like a problem – they are from different plates after all. But all is not as it seems. There are likely to be correlations between plates combined to produce a reportable result due to being run on the same day and by the same operator. That means the observations of the control parameter from these plates are more likely to be similar to each other than those from other randomly selected observations.

The strength of these correlations will depend on the properties of the assay itself. The variance of assay data can be partitioned into two components:

Within-assay variance: The variability between the plates used in each run

Between-assay variance: The variability between the results of each run

The percentage of the total variance attributable to the within- and between-assay variance will always sum to 100%, so we’ll concentrate on the within-assay variance. This is because the degree to which the data will be correlated is directly related to the within-assay variance.

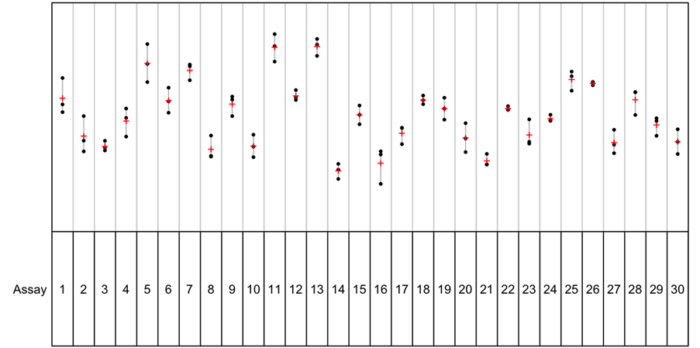

In the plots below, we see data with different percentages of within-assay variance.

In the first plot, the within-assay variance is 93%. The control parameter values are shown as black dots, with the control parameter mean for each assay run shown as a red cross. For this data, we can see visually that, while the values from each individual plate within the assays span a wide range, the means are reasonably similar over the assay runs shown. The control parameter here would not be strongly correlated as the values from plates within each run are not more similar to each other than three randomly selected observations due to the large amount of within-assay variance.

In the second plot, by contrast, the within-assay variance is 12%. This means that the majority of the variability in the data is as between-assay variance. And we can see this on the plot: the individual parameter values for each plate (black dots) are close to the assay means (red crosses) for each assay, but the assay means span a wide range. This means there is a high degree of correlation between the plates within each assay: the control parameter values for the plates within an assay will be far more similar to each other than three randomly selected observations from the dataset at large.

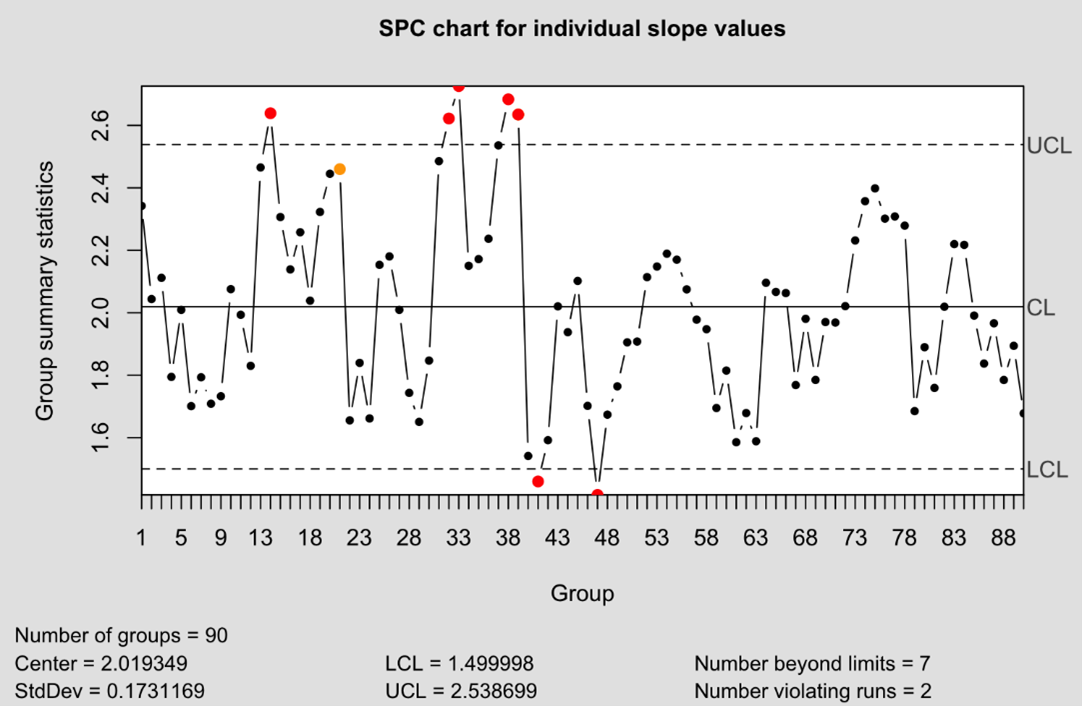

These correlations can have a drastic effect on a SPC process. The plot below shows a control chart using individual values of the reference B parameter. The control limits here were set using the moving range method of estimating the standard deviation. The lines marked UCL and LCL represent the upper and lower alarm limits respectively.

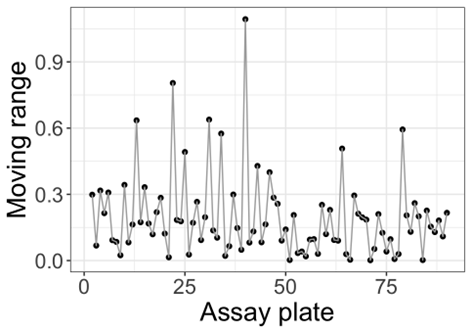

From just 90 observations, seven have breached the defined control limits. That’s a rate of 7%: recall that we expect 0.3% of observations to fall outside these limits by chance, meaning the failure rate is more than ten times higher than expected. The obvious conclusion is that our control limits are too narrow. Why would this be the case? The moving range is based on the absolute difference between consecutive observations. For a three-plate assay format where the plates are highly correlated, this leads to a pattern in the moving range: two small differences between the plates within an assay, followed by a larger difference bridging to the first plate from the next assay run. We can see a pattern such as this emerging in the plot below of the moving ranges of our data.

The result of this pattern of moving averages is that the standard deviation of the data is underestimated: there are more small differences than large differences, meaning the mean moving range is artificially compressed. Since the control limits are set based on this standard deviation, this results in control limits which are too narrow and an artificially elevated failure rate.

Another effect of the correlations is to artificially increase the likelihood of problematic runs in the data. Many commonly implemented rules for monitoring data in SPC involve runs of observations. For example, an investigation might be warranted if nine or more consecutive observations fall the same side of the historic mean. Let’s assume that there’s a 50% chance of any one observation falling above or below the mean. If we assume independence, that means there’s a ![]() chance of a run of nine observations falling entirely above or below the mean by chance. We’d expect to collect 512 observations before such a run occurring naturally. Here, in these 90 observations, we have already observed two such runs: a failure rate of 2% – again, a ten times elevated failure rate.

chance of a run of nine observations falling entirely above or below the mean by chance. We’d expect to collect 512 observations before such a run occurring naturally. Here, in these 90 observations, we have already observed two such runs: a failure rate of 2% – again, a ten times elevated failure rate.

We see this effect since the correlations between plates within the assays mean it’s far more likely that all three of the plates will return observations either entirely above or below the mean. If one of the plates returns a value above the mean, then it is more likely for the other two plates to also return a value above the mean than if three observations were chosen at random. As a result, it’s dramatically more likely for assays with strong correlations to return problematic runs than those without such correlations. Combined with the effect of overly-narrow control limits, this unnecessarily increases the number of costly investigations which, in turn, increases the running costs of the assay.

Thankfully, there is a simple way the problem of correlations can be rectified. Specifically, one can average the control parameter observations from each plate in an assay run to give a single observation for the assay. By averaging away the within-assay variance, we no longer have the problem of the observations of plates within each assay being less variable than three randomly chosen observations, meaning our data no longer contains problematic correlations.

The plot below shows the result of applying this approach to the data shown previously. Notably, the standard deviation of the data has increased when the observations were averaged – ![]() for the unaveraged data while

for the unaveraged data while ![]() when that data has been averaged. This is unusual: generally, the mean of a set of data is less variable than the data itself. Here, this is inverted due to the reduction of variability caused by the correlations between observations from plates within each assay. That the variability has increased when these observations were averaged is an indication that the correlations have been rectified.

when that data has been averaged. This is unusual: generally, the mean of a set of data is less variable than the data itself. Here, this is inverted due to the reduction of variability caused by the correlations between observations from plates within each assay. That the variability has increased when these observations were averaged is an indication that the correlations have been rectified.

Averaging mirrors the approach to tackling correlations within data elsewhere in bioassay – pseudo-replication – where the correlated responses of technical replicates are averaged to ensure key assumptions for statistical inference are followed. In both cases, the downside of this approach is that averaging means we no longer gain information about within-assay or between-replicate variability. This is often outweighed, however, by the benefit of ensuring the assumption of independence is maintained in cases where strong correlations exist within the data.

Assuring the Assumptions

SPC remains a powerful and widely trusted tool for maintaining confidence in bioassay performance during routine manufacturing. However, as we’ve seen, the statistical foundations of SPC rely on assumptions that are not always naturally satisfied in biologic assay systems. Replication across plates, while essential for achieving acceptable precision, can introduce strong correlations that quietly undermine control limits and inflate false alarms if they are not properly addressed.

By understanding how within-assay variance drives these correlations, we can see why traditional individual-value control charts may dramatically overstate instability in otherwise well-behaved assays. The solution, in this case, is reassuringly simple: by averaging correlated plate-level parameters at the assay level, we restore the assumption of independence and recover meaningful control limits that reflect true process behaviour.

As regulators continue to emphasise robust OPPV through frameworks such as USP <1220> and <1221>, it becomes increasingly important that SPC is not just implemented, but implemented correctly. Thoughtful handling of correlation ensures that SPC remains a tool for insight rather than noise – protecting both product quality and the efficiency of assay operations.

Comments are closed.