Statistics is hard, words are harder. So often when working through the statistics behind a bioassay, the correct path is obscured behind a word salad of jargon placed seemingly deliberately to block your passage. Our goal is to make statistics as accessible as possible, which is why we’ve previously examined the different limits one might encounter when conducting a bioassay analysis. Here, we’re going to explore a related concept: intervals. These are crucial concepts which form part of the bedrock of statistical analysis in bioassay, whether that’s in performing suitability tests, evaluating the performance of an assay in validation, or making critical batch release decisions.

The intervals we’ll examine here are closely related concepts: all attempt to quantify the uncertainty of measurement in an assay, but all also tell us subtly different things. They are easily – and understandably! – conflated, which has the potential to cause incorrect decisions. Our aim here, therefore, is to provide a cheat sheet which outlines the definitions of these crucial components of statistical analysis, how and when they are used, and the subtle distinctions between them.

Key Takeaways

-

Confidence intervals express the uncertainty around sample-based estimates, quantifying how reliably repeated samples would capture the true parameter under frequentist assumptions.

-

Prediction intervals use existing data and models to define the range in which a single future observation is expected to fall, and are wider than confidence intervals because they reflect greater variability.

-

Tolerance intervals combine both ideas, defining a range expected to include a specified proportion of the population with a given level of confidence — making them the broadest and most comprehensive of the three.

Note that we won’t be explaining how to calculate the different intervals, though we’ll link to where these guides can be found as appropriate. Instead, we hope to give an intuitive understanding to make your next bioassay analysis as smooth as possible.

Populations vs Samples

Before we begin, we must examine some key context. Whenever we perform an experiment, we are using a measurement to find something out about the world around us. We might use a ruler to measure the length of a rock, or a set of scales to measure its mass, for example. As we know, there will always be some degree of uncertainty in these measurements – our measuring equipment are limited by their precision even before we account for any other factors which might affect the reading. The rock has an intrinsic “true” mass and length, but, due to the measurement uncertainty, we can only ever alight upon an estimate of these properties. The goal of statistics, then, is to quantify the measurement uncertainty and connect our estimates to those “true” properties.

This principle applies to any scientific experiment, including bioassays. A certain test lot will have a “true” relative potency compared to a given reference, but the best we can do to access that property is to find an estimate using a bioassay with all the potential variability that entails. Formally, we refer to the “true” properties as metrics of the population and the results we gain from experiments as estimates based on samples. Further, we refer to properties of the population as parameters, and properties of a sample as statistics.

A useful mnemonic might be to think of voter polling in the leadup to an election: the “true” voting intention of the population of voters is unknown, but we can form an estimate by polling a sample of the population. The voting intention of the whole population would, then, be a parameter, while the voting intention of the voters sampled would be a statistic.

Confidence Intervals

Of the intervals we’ll cover here, confidence intervals are comfortably the most commonly used in bioassay statistics. They are usually quoted alongside a reportable result, such as a relative potency or a concentration measured in an ELISA, as well as on other important properties, such as the relative accuracy and intermediate precision of an assay undergoing validation. Their ubiquity highlights their importance: indeed, in some senses, they are more informative than the reportable result itself. That’s because they provide a direct connection between the reportable result – a statistic based on a sample – and the true properties of the test lot, which are a parameter of the population.

A confidence interval is defined by a confidence level – 90% or 95% confidence are commonly used, but any confidence level between 0% and 100% could theoretically be chosen. The key concept is this: a confidence level gives the proportion of confidence intervals that can be expected to capture the true parameter, under repeated sampling.

Imagine you ran 100 ELISAs on a test lot and found the 95% confidence interval on the measured concentration each time. Providing certain key assumptions hold, you would expect 95 of the 100 confidence intervals to contain the “true” concentration of the lot. You would also expect 5 of the confidence intervals to not contain the “true” concentration – this is a consequence of the random variability of the experiment. Of course, we don’t – and can’t – know which of the confidence intervals contain the “true” concentration and which don’t.

That the definition of a confidence interval is based upon repeated sampling is a sign that it is an object of frequentist statistics. Under the frequentist approach, parameters are fixed, but the information we obtain from sampling is random. The “true” concentration of a lot is a fixed value, but the measurements we take in experiments are affected by random variability. By taking repeated samples, we gain information about this variability and how the statistics we measure in our samples behave. From this behaviour over long-term repeated sampling, we can make inferences about the underlying parameter value.

Crucially, this means that a confidence interval does not represent a region in which the “true” parameter value is expected to fall with a certain probability. A common misconception is that the parameter has a 95% chance of being contained within a 95% confidence interval. This is incorrect: under the frequentist approach, parameters are fixed – they’re either contained within a given confidence interval, or they aren’t. It’s the confidence intervals themselves – based on samples – which are random, leading to the correct claim that 95% of 95% confidence intervals contain the “true” parameter value.

Prediction Intervals

A confidence interval is concerned with defining regions which are likely to contain a desired parameter. A prediction interval tells us something rather different. It uses the experimental data already collected and a statistical model to predict a future observation. Specifically, a prediction interval for a certain input gives us a range of values in which a single, future observation is expected to fall with a given probability.

It is in this sense that a prediction interval is concerned with the distribution of observations. A distribution defines the probability of an observation taking on a certain value. The probability of an observation falling within a certain range is equal to the area under the distribution curve between the bounds of the range. A common distribution is the normal distribution or “bell curve”. Measurements following such a distribution are most likely to have a value close to the peak of the curve, and less likely to take on a value in the tails of the distribution.

A prediction interval is defined by the range which covers the desired portion of the distribution. A common choice might be a 95% prediction interval, which would mean that region defined by the interval contains 95% of the probability associated with the underlying distribution. At this level, we would expect 95% of future observations to fall within the prediction interval and 5% to fall outside.

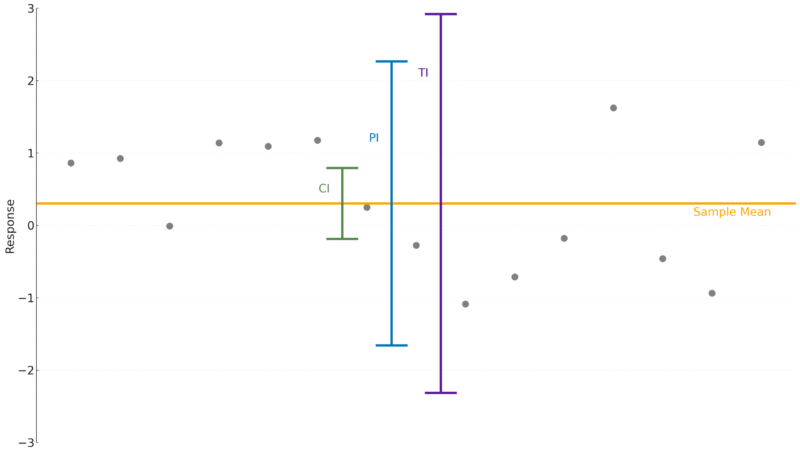

In general, a prediction interval will be wider than a confidence interval estimated from the same observations. A confidence interval reflects the variability of a statistic, such as a sample mean. By contrast, a prediction interval tells us about a single future observation, which will be inherently more variable. As a result, a prediction interval is necessarily wider.

Where might a prediction interval be used in bioassay? Validation is one phase of the bioassay lifecycle in which a prediction interval can be deployed. Specifically, if the prediction interval for the bias is found to be sufficiently small, then that is an indication that the assay is valid at that potency. Prediction intervals can also be deployed retrospectively. For example, Song et al. describe a “prediction region” around a dose-response curve. This functions effectively as a prediction interval at each dose, meaning it gives a region in which future dose-response curves are likely to fall. If a future curve falls outside this region, therefore, this is an indication that there may have been a problem with that assay.

A form of prediction intervals are also used when monitoring bioassays using statistical process control. If a new observation falls outside of alarm limits, for example, then this is an indication that something has gone wrong with the assay system. The alarm limits are often defined by being three standard deviations from the historical mean. Assuming the observation is normally distributed (and has known mean and standard deviation), this means we expect 99.7% of observations to fall within the alarm limits. In essence, therefore, alarm limits define a 99.7% prediction interval for the observation being monitored.

Tolerance Intervals

Like the confidence interval, a tolerance interval is concerned with the properties of the population – the “true” properties of the system we are interested in. And, in a sense, it combines the concepts of prediction and confidence: a tolerance interval defines a region in which a given proportion of the population is expected to fall with a given probability. That means, uniquely among the intervals we’ve discussed, a tolerance interval is defined by two properties: a proportion and a probability. So, we might find the 99%/95% tolerance interval on a concentration, say, which would be interpreted as the region in which at least 99% of measured concentrations would fall with 95% confidence.

Assuming a parameter follows a normal distribution, the “true” value of the parameter can be thought of as the mean of the distribution. Whereas a confidence interval is concerned with the location of this mean, a tolerance interval provides a range which contains a given proportion of the distribution itself – this is the proportion we quote when defining the interval. So, a tolerance interval covering a 99% proportion of the population would contain at least 99% of the observations.

Imagine you are in charge of setting specification limits for a critical quality attribute across 100 different products, and you choose to use a tolerance interval to do so. Let’s say you construct a 99%/95% tolerance interval for each product. Of those 100 tolerance intervals, you would expect 95 of them to correctly cover at least 99% of the observations of the critical quality attribute for the associated product. At the same time, you could expect that, for five of the products, their tolerance interval would not cover the correct proportion.

Because a tolerance interval tells us about the behaviour of a measurement under repeated sampling – this is the confidence part of the definition of the interval – a tolerance interval is wider still than a prediction interval which covers the same proportion of the population. That is, a tolerance interval with a 99% proportion would be wider than a 99% prediction interval. In essence, we are now accounting for the random error associated with our experiment, so the interval needs to be slightly wider to achieve the desired properties.

Tolerance intervals can be used similarly to prediction intervals in bioassay. In a validation study, if the tolerance interval on the reportable result at a 100% potency level lies within the specification limits, this could be used as evidence that the assay is valid at that potency. Similarly, for a potency level which was not expected to provide a result within the specification limits (e.g. 50% potency for spec limits of 0.71 – 1.43), a tolerance interval which fell outside the specification limits would indicate the desired behaviour of the assay.

Each of the intervals we’ve examined here quantifies uncertainty, but each does so for a different target: the parameter, the future observation, or the population itself. Confidence intervals help us understand how our experimental estimates relate to the unknown truths of the biological systems we’re studying. Prediction intervals shift the focus from parameters to future measurements, letting us forecast what we should expect from an assay that behaves as it always has. And tolerance intervals widen the view still further, describing the spread of results we can expect from an entire population with a defined level of confidence.

Understanding which interval answers which question is key to drawing correct conclusions, defending validation results, and making robust release decisions. Clarity about terminology may not make statistics easy, but it can clear a path through the analysis.

Comments are closed.