Previously, we examined the reasons why one might consider attempting to identify and remove outliers from bioassay data. From a scientific perspective, omitting any collected data is never ideal, but true outliers are not part of the natural variability of the assay so ought not be included alongside legitimate observations. And, as we discovered through a simulation analysis, outliers reduce the accuracy and precision of relative potency measurements. From a practical perspective, this has the potential to increase failure rates and, in turn, the expense of running the assay. We can, therefore, conclude that it is often a good idea to remove outlying observations before analysis.

This, however, presents a challenge. How do we determine whether an observation is truly an outlier? Here, we’ll address this question from the perspective of different stakeholders in a bioassay, and examine the performance of some commonly used outlier detection techniques for single point outliers.

Key Takeaways

-

True outliers distort assay precision and accuracy, increasing variability and potential assay failure rates. Although data omission is not ideal, correctly identifying and removing outliers enhances analytical integrity.

-

Grubbs’ test is highly specific and minimises false positives but can miss true outliers, making it suitable when data are limited. Studentised Residuals are more sensitive and detect more true outliers but risk misidentifying legitimate data points.

-

Removing outliers improves assay accuracy but can also artificially compress variability, affecting parallelism testing. Careful application of statistical methods and awareness of test assumptions (e.g. normality for Grubbs’ test) are vital.

From the statistical, scientific, and regulatory definitions of an outlier which we’ve previously established, there are a couple of factors which can be agreed on as distinguishing an outlier from other observations. An outlier is an observation which is not consistent with the variability of other observations from the assay. Critically, this difference is a result of some (usually unintentional) change to the assay process, such as an operator error or equipment malfunction.

We can usually identify the first of these properties visually from a plot of the data. An outlier will be further away from other observations than is usual for data in the assay. It is, however, impossible to determine visually whether such an observation is truly from a different statistical population to the other observations or if it is simply a rare chance occurrence which is part of the natural variability of the assay. That, along with the subjectivity of visual assessments, is why visual outlier identification should never be used for anything beyond guiding further investigations. Visual examination of data can be powerful and is absolutely encouraged, but additional information should always be gathered before any official decisions are made.

How then can we decide whether an unusual observation truly belongs to a different statistical population? The most common way this is possible is through early acknowledgement of a problem having occurred in the lab. If an analyst spots that, say, a sample has been in the assay, then that fact can be recorded and the data removed when it comes to analysis. In such a case, we have explicit reason to believe that any observations from that sample will be from a different population to others in the assay, meaning we are justified in removing them.

This evidence, however, will not always be immediately available. It is not difficult to imagine a scenario where an observation with unusual variability is spotted in the data, but there is no obvious reason why it might have occurred. In some cases, it may be possible to recover a cause from lab records, but even this is often not possible. In this scenario, we must turn to statistical outlier detection methods. These tests seek to determine the likelihood that an observation originates from a different population based on the statistical properties of the data, such as its standard deviation.

Such tests function on the principle that, for normally distributed data, most observations of a population will occur near the population mean. The number of expected observations decreases predictably – based on the population standard deviation – the further away from the population mean one gets.

Imagine we were measuring the heights of a class of 20 elementary school students. If 19 of the 20 students had heights between 3’ and 4’, but one was 6’ 2”, we might reasonably conclude that the latter student was not, in fact, an elementary school student and had been included unintentionally. That degree of variability would not be expected by chance, so is unlikely to be part of the natural variability of the heights of the class. A similar principle applies in outlier tests for bioassays: if an observation is sufficiently far away from the mean of the distribution from which it is supposed to be drawn that it is unlikely to have occurred by chance, we can conclude that it does not belong to that distribution after all.

Now, this principle is not infallible. Low probability events are not impossible events, and there will inevitably be scenarios where a point with improbably high variance occurs by chance alone. One does not have to look in too many elementary school classrooms before one finds a 7-year-old who has had an extraordinarily early growth spurt. As a result, statistical outlier tests will always have a failure rate where they identify legitimate observations as outliers. This is partially controlled by a threshold in the process of performing the test, but the design of the test will also affect this failure rate. Of course, we don’t want to raise this threshold too high as true outliers may then be missed: the implementation of any statistical outlier test will require a balance between ensuring true outliers are detected and avoiding misidentification of legitimate observations as outliers.

Two commonly used statistical tests for outlier detection are Grubbs’ Test and Studentised Residuals (SR). Both can be used as model-based outlier detection methods, meaning they require a statistical model be fit to the observations before determining whether any of those observations are outlying. Alternative approaches which detect outliers based on an observation’s relationship to its dose group are also commonplace. The advantage of a model-based approach is that it considers all the data from the assay at once, rather than looking at each dose group one by one, .

Let’s take a look at each methodology in turn.

Grubbs’ Test

Grubbs’ test utilises a hypothesis test to determine whether an observation is likely to belong to the same statistical population as other observations in a dataset. This is based on the residuals of the observations with respect to a fitted statistical model. In this context, a residual is the difference between an observation and the response “expected” by the fitted model at that concentration. That means the residual of an observation increases the farther that point is away from the fitted curve.

For bioassay data, the implementation of Grubbs’ test looks like this:

- Fit a statistical model to the collected bioassay response data.

- Calculate the residual of each response to the fitted model, and find the point with the largest residual.

- Calculate the Grubbs’ test statistic for the largest residual, and find the corresponding p-value. If the p-value is less than the significance level for the test (

is standard), then we have evidence that the response does not belong to the same statistical population as the other data, meaning it is an outlier.

is standard), then we have evidence that the response does not belong to the same statistical population as the other data, meaning it is an outlier. - Remove the outlying point and repeat from step 1 until no further outliers are detected.

Note that Grubbs’ test assumes that the residuals are normally distributed.

Studentised Residuals

Outlier detection based on studentised residuals works similarly to Grubbs’ test, but also considers how influential any one response is on the model fit by incorporating the leverage of each response. The larger the leverage of a response, the larger the influence of that response on the model fit, all else being equal. Importantly, a large residual and high leverage indicates that response was strongly influential on the fitted model.

The test works as follows:

- Fit a statistical model to the collected bioassay response data, and calculate the residual of each response to the model.

- Calculate the leverage of each response.

- Remove each response in turn and refit the model. Find the standard deviation of the remaining data once each response has been removed.

- Calculate the externally studentised residual (ESR) for each response

. This is given by:

. This is given by:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ ESR_i=\frac{r_i}{\sigma_i\sqrt{1-l_i}} \]](https://www.quantics.co.uk/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-95d8d71b72c8b8ee5c2920ba46f63445_l3.png)

where:

is the residual of the response to the originally fitted model.

is the residual of the response to the originally fitted model. is the standard deviation of the response data with the response removed.

is the standard deviation of the response data with the response removed. is the leverage of the response.

is the leverage of the response. - If the ESR of any response is greater than some threshold (as standard), then that response is deemed an outlier.

When will the ESR of a response be large? From the formula, we can see that the larger the residual and the leverage of a response, then the larger its ESR will be. However, the more variable the rest of the data – the larger the standard deviation with the response removed – the smaller the ESR. This means that influential responses which show unusually large variability compared to the rest of the dataset will have large ESR values, which makes it a great tool for identifying outliers.

To demonstrate the performance of these approaches to outlier identification, we performed a simulation study consisting of analysis of 1000 datasets. These datasets were similar to those used in the study conducted in part one of this series. Specifically, six dose groups of three replicates each were generated for both a reference and a test sample. These had the same curve parameters: the “true” relative potency of the test sample was 100% in all cases. Exactly one outlier was then added to the data for the test sample by selecting a replicate at random and replacing it with a replicate shifted by ![]() in the y-direction, with the direction of the shift depending on whether the replaced replicate was above or below its dose group mean.

in the y-direction, with the direction of the shift depending on whether the replaced replicate was above or below its dose group mean.

All 1000 datasets were then analysed using two different QuBAS methods. One used Grubbs’ test for outlier identification and removal with a threshold of ![]() . The other used Studentised Residuals with a threshold of

. The other used Studentised Residuals with a threshold of ![]() . Both methods also included an F Test for parallelism with a significance level of

. Both methods also included an F Test for parallelism with a significance level of ![]() . If a dataset did not pass this parallelism test, it was not included in evaluations of the relative potencies produced using each analysis method. Note that the simulated model parameters were identical for test and reference, i.e., the data was simulated such that the test and reference were truly parallel, with any differences when analysed a result of random variability.

. If a dataset did not pass this parallelism test, it was not included in evaluations of the relative potencies produced using each analysis method. Note that the simulated model parameters were identical for test and reference, i.e., the data was simulated such that the test and reference were truly parallel, with any differences when analysed a result of random variability.

Once the analyses were complete, the results for each dataset were categorised according to how many outliers were detected and removed during the analysis. We designated this number as ![]() . The categories were:

. The categories were:

![]() : No observations were detected as outliers

: No observations were detected as outliers

![]() : The added outlier was detected and removed

: The added outlier was detected and removed

![]() : Multiple observations – including the added outlier – were detected and removed as outliers

: Multiple observations – including the added outlier – were detected and removed as outliers

Note that there were no datasets for which ![]() where the added outlier was not among the observations detected as outliers.

where the added outlier was not among the observations detected as outliers.

The analysis results were once again evaluated using Average Absolute Deviation (AAD) and the geometric mean of the precision factor (PF). These are outlined in detail in part one of this series. In short, is a measure of the average difference between the measured relative potency from the analysis and the true relative potency of the test sample, which was simulated to be 100%. It really encapsulates measurement error, but can be thought of in this context as a way to discuss the accuracy of the analyses. The precision factor, defined by the ratio of the upper and lower confidence limits of the relative potency result, details the precision of an individual relative potency measurement.

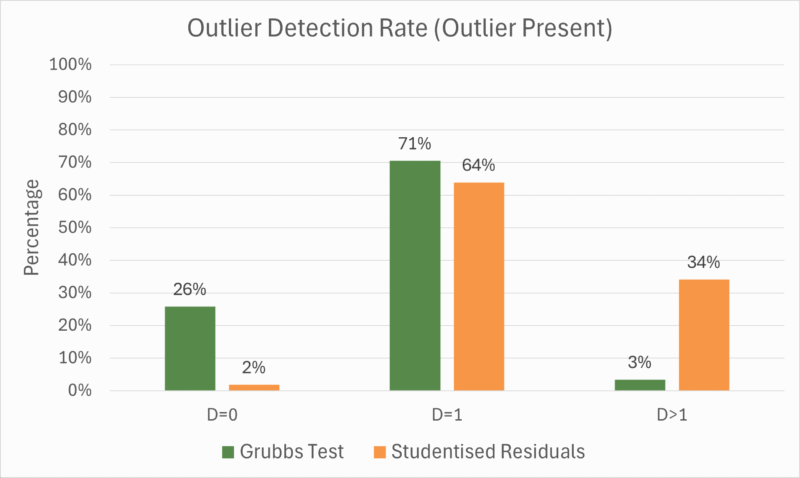

The table below shows results from the analyses broken down by detection category. The table includes the number of datasets which fell into each category, the percentage of those datasets which passed the parallelism suitability test, and the evaluation of those datasets according to the precision factor and the AAD. Meanwhile, Figure 1 shows the percentage of datasets in each detection category for each outlier detection method.

From the results, we see that both methods of outlier detection have similar “success” rates, if we define success as ![]() . Recall that these are the cases where the deliberately added outlier alone was detected and removed. The success rate for Grubbs’ test (71%) was slightly higher than for Studentised Residuals (64%).

. Recall that these are the cases where the deliberately added outlier alone was detected and removed. The success rate for Grubbs’ test (71%) was slightly higher than for Studentised Residuals (64%).

Notably, however, the failure modes for the two methods are different. Grubbs’ test was far more likely to detect no outliers at all (![]() ) than Studentised Residuals (26% vs 2% of datasets, respectively), while Grubbs’ test was far less likely to detect multiple outliers (

) than Studentised Residuals (26% vs 2% of datasets, respectively), while Grubbs’ test was far less likely to detect multiple outliers (![]() ) than Studentised Residuals (3% vs 34%). This means that Grubbs’ test and Studentised Residuals have different ideal use cases as set up in this study.

) than Studentised Residuals (3% vs 34%). This means that Grubbs’ test and Studentised Residuals have different ideal use cases as set up in this study.

Grubbs’ test here is a highly specific test: it gives very few false positives at the cost of more frequent false negatives. In this context, this specificity meant that the test was unlikely to detect more than one true outlier, but this came at the cost of sometimes missing the added outlier. Grubbs’ test might, therefore, be used when data is limited: we might prefer to miss an outlier than to misidentify and remove a legitimate observation.

By contrast, Studentised Residuals is here a highly sensitive outlier test. It is far more likely to give false positives – i.e. misidentified outliers – than false negatives. As such, we might choose to use Studentised Residuals when missing an outlier could be a critical issue for the analysis.

For both detection methods, the AAD and Geomean(PF) were greatest when ![]() . This is unsurprising: the added outlier is missed in these cases. As we demonstrated in part one, the presence of an outlier decreases the precision of a relative potency measurement as well as increasing the measurement error. As we might expect, therefore, the AAD is lowest when ; that is, the measured relative potency is closest to the true relative potency when the true outlier alone is removed. The Geomean(PF) however, is minimised when

. This is unsurprising: the added outlier is missed in these cases. As we demonstrated in part one, the presence of an outlier decreases the precision of a relative potency measurement as well as increasing the measurement error. As we might expect, therefore, the AAD is lowest when ; that is, the measured relative potency is closest to the true relative potency when the true outlier alone is removed. The Geomean(PF) however, is minimised when ![]() . This is an artefact of the preferential removal of the most variable points: when multiple observations are removed, it is only those with the highest variability which are eliminated. This means that the overall variability of the assay is reduced, artificially compressing the confidence interval on the relative potency result

. This is an artefact of the preferential removal of the most variable points: when multiple observations are removed, it is only those with the highest variability which are eliminated. This means that the overall variability of the assay is reduced, artificially compressing the confidence interval on the relative potency result

We also see the effect of artificially reduced variability on the outcome of the suitability test for parallelism. Since the significance level of the test was ![]() , we would expect 99% of assays to pass, with 1% failing by chance. And, indeed, when outlier detection succeeded – when

, we would expect 99% of assays to pass, with 1% failing by chance. And, indeed, when outlier detection succeeded – when ![]() – we saw this almost exactly for both tests. When

– we saw this almost exactly for both tests. When ![]() , however, the failure rate of the parallelism test was inflated. For Studentised Residuals, approximately 6% of assays failed on parallelism when

, however, the failure rate of the parallelism test was inflated. For Studentised Residuals, approximately 6% of assays failed on parallelism when ![]() , while 12% of assays failed parallelism for the same category when using Grubbs’ test, albeit for a small sample size.

, while 12% of assays failed parallelism for the same category when using Grubbs’ test, albeit for a small sample size.

This is a direct result of a flaw in the F Test: as we have outlined elsewhere, the F Test can fail for very precise assays. When we remove the most variable observations from the assay data, the artificially reduced variability leads to excessive failures of the F Test for parallelism. This demonstrates that it is often worth considering other approaches to parallelism testing if the test is not behaving as expected.

As we’ve seen, outlier identification is a complex process. Ideally, outliers can be caught at source by information from the lab, but often statistical detection methods are required. We’ve examined two such methods here – Grubbs’ test and Studentised Residuals – and found that each have their own unique properties and, therefore, use cases. One question which is as yet unanswered is the degree to which misidentifying observations as outliers when no outliers are present is problematic. We’re going to investigate this in the next part of this series.

Comments are closed.